ReadyMade: Tell us a little bit about this work, your ideas behind it, your influences, etc.?

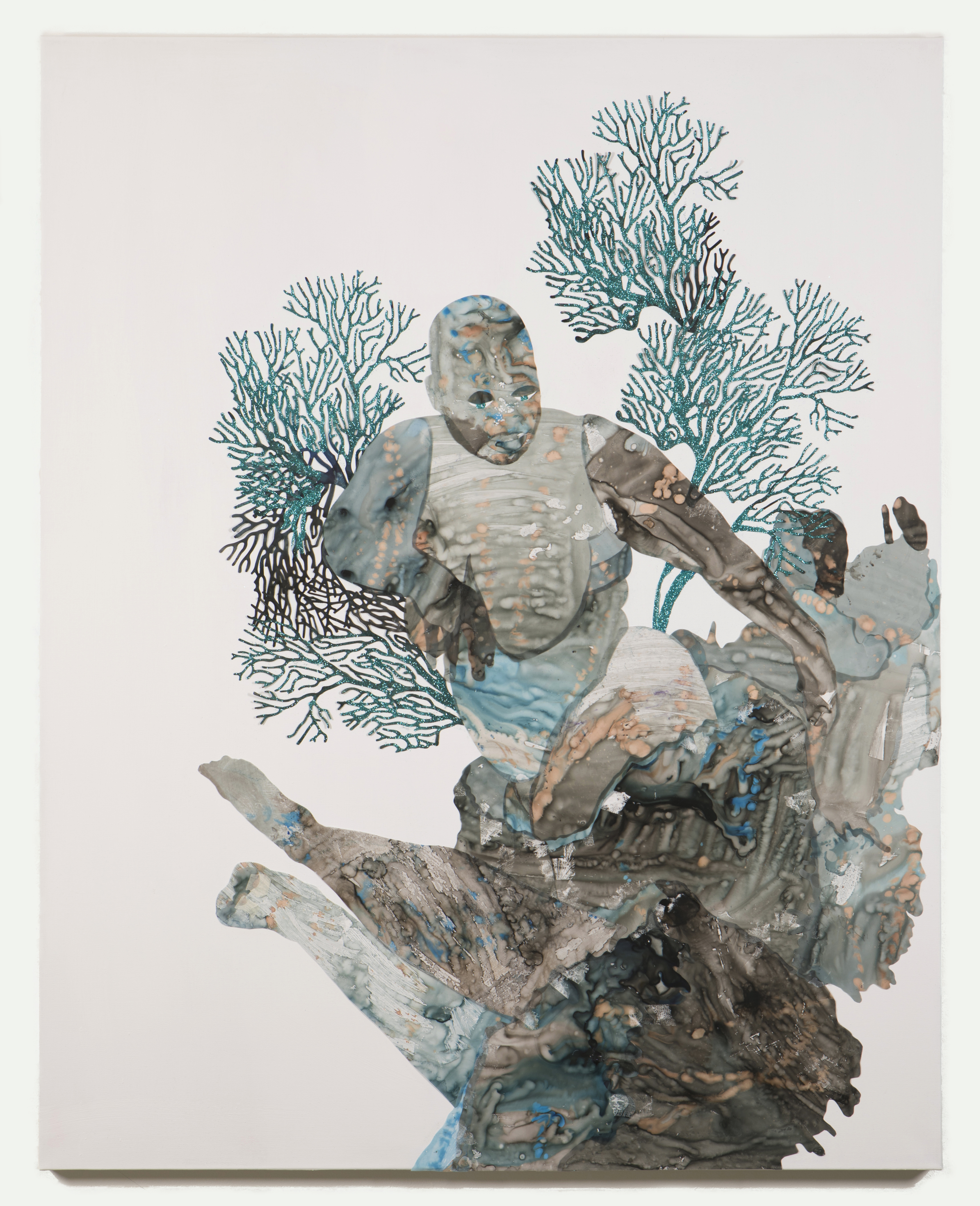

M. Florine Demosthene: I think part of it was creating a mythology that doesn't exist, in a way. I’ve been learning a lot from West African mythology, which the majority of was based on the male spirit. So I've been very much interested in the idea of the feminine. How to create the female spirit. How to put the divine in our world in a way.

RM: Do you feel like there's the connection between whatever this kind of myth you're creating is and how you view contemporary society? What do you see the connection being?

M. FD: I think I borrow a lot from it. The way we move through the world and make decisions. But it's been more of how we maneuver our mental space and obviously technology changes all of that, how we deal with one another, and just, how we see ourselves in the world. It's more that approach, a dissecting of these types of things, of how we come to each other and how I can put that in without necessarily saying that explicitly.

In Coversation with...

M. Florine Demosthene

RM:You have been called a “diasporic” practitioner. What about that do you try to convey in your work?

M. FD: That probably applies really well to what I'm doing, because I was living in Accra and I would go between Accra and Johannesburg. So the bulk of what I was doing was in West Africa and Southern Africa. Then having the Caribbean roots and also being from New York, sometimes people don’t know what to do with me. It's sort of a bizarre thing. Now, it's sort of trendy, but four or five years ago, it was not right to do that. So for me, I was interested in seeing black people in this way as well. How are African people in the United States, African people in the Caribbean, etc.? I was going to see African people in Africa and try to understand the things that remain within us, like our perceptions of things, and how much of it is filtered through European and American influence.

There wasn't necessarily any particular thing I was searching for but I remember when I first got to Ghana, I asked every single person I met about love. What is love? So, you know, I have a posse of friends now and we’re talking about what they think love is, and it was their perception that love or an expression of love was a Western thing. They said, “here we don't show love like this,” or “we don’t express it like that.” And then I would argue, “so why do you have SO many songs about love then?” If you look at the core Ghanian music of the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s, 90% of the music is about love. So how could you possibly say that?

I didn't actually approach it from a place of race or gender or anything like that. I approached it from a place of humanity, from exploring people at the core. At the end of the day we all want the same things.

RM:After hearing all of these different ideas from all these different perspectives, how do you reconcile everything and then turn it into the work that you've been making?

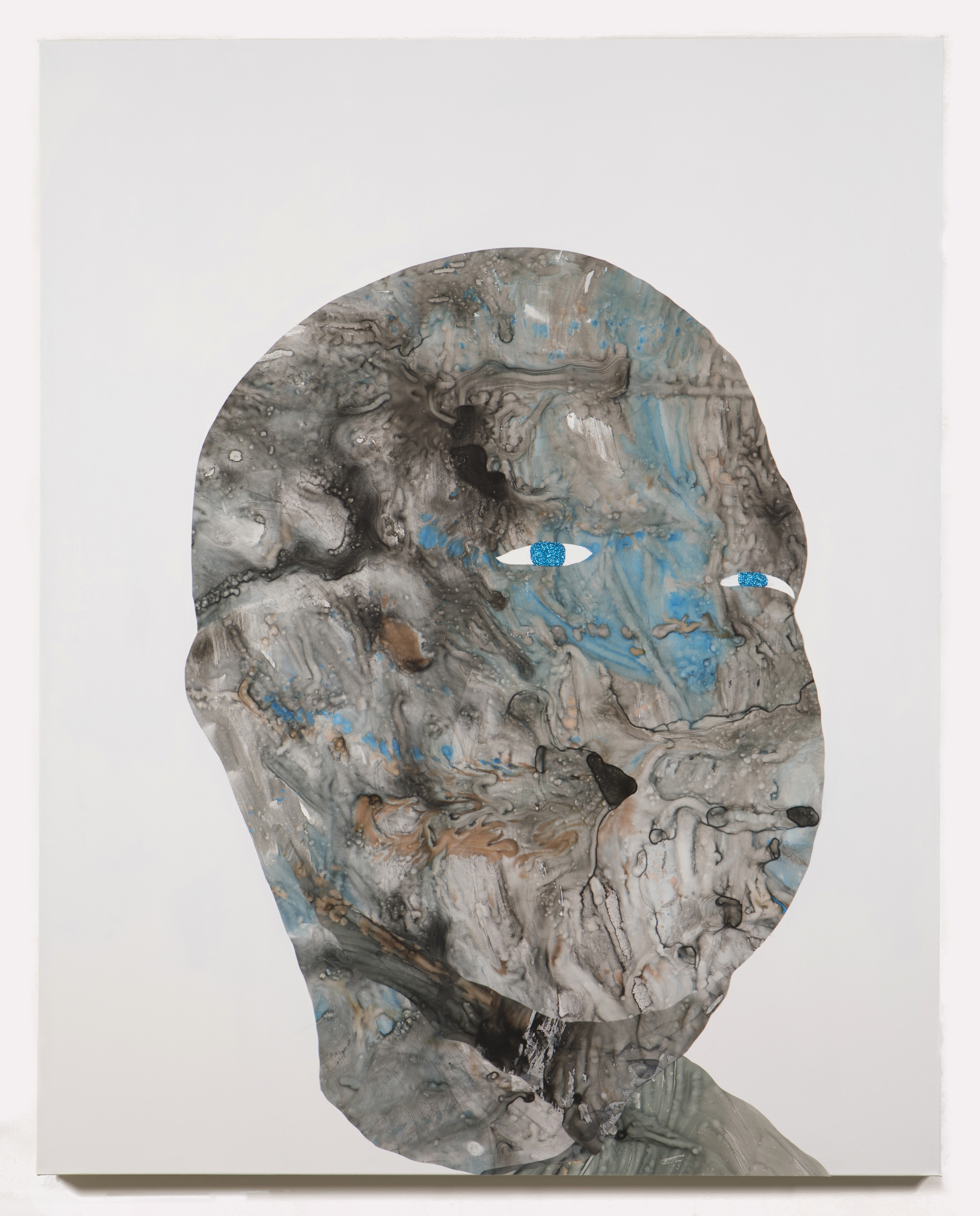

M. FD: It was after the first trip to Ghana that I started thinking about the idea of the Heroine. Through having all these different conversations about love, naturally other ideas came up and I realized everything is about the “mental space”. I felt like those were the things that connected everyone.

RM: The heroine in your work seems to be autobiographical, can you talk about that?

M. FD: Well, I use myself because...I'm here and I'm reliable. I show up to work and, honestly, I don't have to pay. So that really became a thing of convenience to use myself. And also, to me, relinquishing a lot of fears that I had about my body, what people would think, all of these things. After a while, when I'm working, I don't even see me. It's funny, I will be just working on something and it takes me a while to realize it’s actually me. At this point I’ve done it so many times I’m not critical like I used to be when I first started.

M. FD: That probably applies really well to what I'm doing, because I was living in Accra and I would go between Accra and Johannesburg. So the bulk of what I was doing was in West Africa and Southern Africa. Then having the Caribbean roots and also being from New York, sometimes people don’t know what to do with me. It's sort of a bizarre thing. Now, it's sort of trendy, but four or five years ago, it was not right to do that. So for me, I was interested in seeing black people in this way as well. How are African people in the United States, African people in the Caribbean, etc.? I was going to see African people in Africa and try to understand the things that remain within us, like our perceptions of things, and how much of it is filtered through European and American influence.

There wasn't necessarily any particular thing I was searching for but I remember when I first got to Ghana, I asked every single person I met about love. What is love? So, you know, I have a posse of friends now and we’re talking about what they think love is, and it was their perception that love or an expression of love was a Western thing. They said, “here we don't show love like this,” or “we don’t express it like that.” And then I would argue, “so why do you have SO many songs about love then?” If you look at the core Ghanian music of the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s, 90% of the music is about love. So how could you possibly say that?

I didn't actually approach it from a place of race or gender or anything like that. I approached it from a place of humanity, from exploring people at the core. At the end of the day we all want the same things.

RM:After hearing all of these different ideas from all these different perspectives, how do you reconcile everything and then turn it into the work that you've been making?

M. FD: It was after the first trip to Ghana that I started thinking about the idea of the Heroine. Through having all these different conversations about love, naturally other ideas came up and I realized everything is about the “mental space”. I felt like those were the things that connected everyone.

RM: The heroine in your work seems to be autobiographical, can you talk about that?

M. FD: Well, I use myself because...I'm here and I'm reliable. I show up to work and, honestly, I don't have to pay. So that really became a thing of convenience to use myself. And also, to me, relinquishing a lot of fears that I had about my body, what people would think, all of these things. After a while, when I'm working, I don't even see me. It's funny, I will be just working on something and it takes me a while to realize it’s actually me. At this point I’ve done it so many times I’m not critical like I used to be when I first started.

RM: Do you disassociate yourself from what you're seeing a little bit?

M. FD: Yeah. I would say quite a bit. And I don’t get upset over it, like trying to edit things and make things look perfect. I think I got to the point where I could say, I don’t care, when I was in South Africa. I start by doing digital print outs first to work off of. Before that I always did them in private. There was nothing I could do in South Africa. I was like, the hell with this, I'm going to a coffee shop. This guy was picking it up off of the printer and holding it. So I walked by and was suffering for about a minute, and then just told myself to get over it. If people are going to have these issues, it's not my issue.

RM: Talk about the male gaze.

M. FD: Exactly. I mean when I print in a public place of course I get little laughs and giggles and you know what? I don’t care.

RM: Do you feel like it’s your alter ego?

M. FD: No, I still feel it's me. It's definitely me. But it's like working from myself instead of an object for still life. You know, you have attachments to these objects, but the reason why you use these objects is to convey a particular meaning in the work that you're doing. After a point you don't necessarily see the objects anymore because you know them, you know how to draw them, you know what they look like and so it becomes about something else entirely.

RM: For this work in particular, how does this figuration unfold in this story?

M. FD: It’s really a story within a story from my Armory show in November. This work is more of an exploration of these sort of mythical figures. I like looking at feminine deities and the way they are always sort of connected with water. Water is a healing element, but it's also an element of fear and element of transportation. I was looking at all of these different aspects of feminine energy, so I wanted to tap into some of that without being so explicit about it.

RM: And now to the question of the hour. Given everything that's happening, the whole world really being forced to slow down and change, how has that affected your work? How has that affected your attitude towards creating?

M. FD: Well, I think we went through a very long period when art wasn't about much. And I can say that boldly. If you are a person who is not a white male, then you fall into this “other” category. There has, of course, been other art but it was more about a “wow” factor and I found it really hard to find work that moved me, work that I had a visceral reaction to. But I think now, maybe for the past five or six years, I think we’re starting to see this resurgence of work where artists are just not afraid. I think sometimes artists get in the mind space of making work that can sell versus making work that they’re interested in.

Now with the slowdown, I think people are gonna really ask themselves what they are about. I don't think it's going to be about, you know, what am I doing about something, or what do I want to do about something, but instead it's going to be, what am I about? What do I stand for? What is the core essence of who I am? Because there's no going back.

You know, it's not about making all this money, not about the neighborhood you live in or the person you're dating and who they're connected to. People now have to really say, “this is what's important to me.” So I think you’re going to start to see work that is a lot more authentic and a lot less disconnected from nature in the art world.

M. FD: Yeah. I would say quite a bit. And I don’t get upset over it, like trying to edit things and make things look perfect. I think I got to the point where I could say, I don’t care, when I was in South Africa. I start by doing digital print outs first to work off of. Before that I always did them in private. There was nothing I could do in South Africa. I was like, the hell with this, I'm going to a coffee shop. This guy was picking it up off of the printer and holding it. So I walked by and was suffering for about a minute, and then just told myself to get over it. If people are going to have these issues, it's not my issue.

RM: Talk about the male gaze.

M. FD: Exactly. I mean when I print in a public place of course I get little laughs and giggles and you know what? I don’t care.

RM: Do you feel like it’s your alter ego?

M. FD: No, I still feel it's me. It's definitely me. But it's like working from myself instead of an object for still life. You know, you have attachments to these objects, but the reason why you use these objects is to convey a particular meaning in the work that you're doing. After a point you don't necessarily see the objects anymore because you know them, you know how to draw them, you know what they look like and so it becomes about something else entirely.

RM: For this work in particular, how does this figuration unfold in this story?

M. FD: It’s really a story within a story from my Armory show in November. This work is more of an exploration of these sort of mythical figures. I like looking at feminine deities and the way they are always sort of connected with water. Water is a healing element, but it's also an element of fear and element of transportation. I was looking at all of these different aspects of feminine energy, so I wanted to tap into some of that without being so explicit about it.

RM: And now to the question of the hour. Given everything that's happening, the whole world really being forced to slow down and change, how has that affected your work? How has that affected your attitude towards creating?

M. FD: Well, I think we went through a very long period when art wasn't about much. And I can say that boldly. If you are a person who is not a white male, then you fall into this “other” category. There has, of course, been other art but it was more about a “wow” factor and I found it really hard to find work that moved me, work that I had a visceral reaction to. But I think now, maybe for the past five or six years, I think we’re starting to see this resurgence of work where artists are just not afraid. I think sometimes artists get in the mind space of making work that can sell versus making work that they’re interested in.

Now with the slowdown, I think people are gonna really ask themselves what they are about. I don't think it's going to be about, you know, what am I doing about something, or what do I want to do about something, but instead it's going to be, what am I about? What do I stand for? What is the core essence of who I am? Because there's no going back.

You know, it's not about making all this money, not about the neighborhood you live in or the person you're dating and who they're connected to. People now have to really say, “this is what's important to me.” So I think you’re going to start to see work that is a lot more authentic and a lot less disconnected from nature in the art world.